Parashat Lech Lecha: Avraham, Father of the Jews and the Converts

The change of Avraham’s name represents a change in his status. He becomes the father of all converts, which enables them to read the biblical text accompanying the offering of bikurim. Beit She’an is one of Israel’s ancient cities that is outstanding in its fertile soil and enjoys a special halachic status. In the past it was a mixed city, but now it is completely Jewish.

Avraham: The Father of the Jews and the Converts

“You shall be the father of a multitude of nations … I will make you most exceedingly fruitful, and make nations of you, and kings will descend from you” (Gen. 17:4-6).

We learn in the name of R. Yehuda: A convert who offers first fruits reads [the text], for what reason? As it is written: “Since I have made you the father of all nations.” Previously you were the father of Aram, and now you are the father of all the nations (J Bikurim 1d).

Do Converts Read out the Bikurim Text?

At first blush, it seems that this verse and its interpretation are associated only with the realms of Agada and philosophy. However, R. Yehuda extrapolates from them a practical halacha on a sensitive topic: the possibility for converts to offer bikurim, the first fruits, and read out the biblical verses associated with bikurim just like any other Jew. Yet, the halacha that R. Yehuda learns from this verse contradicts an explicit Mishna (Bikurim 1:4):

The convert offers [bikurim] and does not read [the text], since he cannot say “That G-d swore to our forefathers to give us” (Duet. 26:3). If his mother is Jewish he offers and reads. When he prays [the amida] privately, he says: “The G-d of Israel’s forefathers.” When he prays in a synagogue, he says, “The G-d of your forefathers.” If his mother is Jewish he says, “The G-d of our forefathers.”

The halachot stated in the Misha above label converts as second class Jews to a certain extent. This, obviously, is not supposed to diminish the love and warmth we are commanded to show converts—more than all other Jews—but it certainly relegates them to the sidelines: the Land of Israel was not given to them, the holy forefathers are not truly theirs. Rabeinu Tam rules according to this Mishna (Bava Batra 81a s.v. lemeutei).

However, this commentary in the Jerusalem Talmud above, brought in the name of Rabbi Yehuda, has the exact opposite approach: According to this view, converts can offer bikurim and also read out the biblical passages, and certainly pray to “the G-d of our forefathers,” since Avraham Avinu is considered his father—“Now you are the father of all the nations.” The Rambam rules according to this approach (Bikurim 4:3), and used this ruling to encourage Ovadia the convert, one of the righteous converts of his generation, in a letter he wrote to him. The Ri in Tosafot (Bava Batra, ibid.) also rules like the Jerusalem Talmud.

Two Sides of the Co(i)nvert

It seems that this dispute presents two aspects of the way converts belong to the Jewish people. On the one hand, converts are not biological descendants of the holy forefathers, and neither do they receive a portion in the Land of Israel as an inheritance. On the other hand, however, converts are the spiritual progeny of Avraham Avinu—perhaps even more so than are those born Jewish, since Avraham left the false path of his forefathers and clung to the Divine Presence, and this is exactly what the converts have done as well. In this way, converts are certainly worthy of being considered the sons and daughters of Avraham Avinu.

It is interesting to note that the verse from the passage recited when offering bikurim fits in with the opinion opposing the one Rabbi Yehuda extrapolated from the verse in our parasha. It describes the Land of Israel as the land “G-d swore to our forefathers to give to us” (Duet. 26:3). This statement implies that converts do not receive inheritance from the forefathers—just as in cases where a rabbi has a disciple who follows in his footsteps and as son who does not, the inheritance goes to the biological son and not to the disciple. But it doesn’t end here, since inheriting a portion of the Land of Israel does not necessarily follow the norms of inheritance from father to son: Yishmael and Eisav did not inherit a portion of the Land of Israel, for example. Neither did Reuven merit a double portion, the Torah-mandated inalienable right of firstborns. Even the apportioning of the country was done according to those who exited Egypt and not according to the regular laws of inheritance, whereas each generation inherits from the preceding generation. For this reason, it sees that even meriting a portion of the Land of Israel does not necessarily stem from the regular laws of inheritance.

What, then, is the basis for the right to a portion of the Land of Israel? It seems that a portion of the country is much more than just a real estate asset. It is primarily a spiritual asset, where each and every person is supposed to rectify the specific and unique aspect of the revelation of G-d’s kingship in the material world in general and on the Land of Israel’s physical soil in particular. Converts, who themselves have embarked on a very difficult spiritual journey, it seems, find it difficult to go the extra mile and reveal G-dliness within the material world. This is why they do not have a right to a portion of the Land of Israel. Biological Jews, born and bred on the connection between heaven and earth, who have a physical Jewish body that is suited for this mission (as an inheritance from Avraham Avinu), can go this extra mile. However, when Moshiach comes, a time when many spiritual barriers will be removed, the converts will also receive a portion in the Land of Israel and they will then be able to make this rectification as well (Kohelet Raba).

Avraham Avinu’s Path

The above is not only true for how we relate to converts. We too, the children and disciples of Avraham Avinu, should recognize both aspects ourselves: First, we must be eternally grateful to Hashem that we merited being the children of Avraham Avinu, and that we were born into a much more rectified spiritual state. Yet, this does not mean that we cannot follow Avraham’s path of disconnecting ourselves from idol worship. Within us there is a “false god”—the evil inclination tries to persuade us to sin; although being the children of Avraham Avinu makes it easier for us to fight it, the battle with this false god cannot be won solely thanks to our pedigree. Just like our Avraham, we must try to discern what the true inner voice that guides us, and make sure it is the voice of Hashem and not that of the evil inclination. We must even be willing to smash the idols within us when need be.

R. Yehoshua b. Zeruz, the son of R. Meir's father-in-law, testified before Rabbi that R. Meir ate a leaf of a vegetable in Beit She’an [without tithing it]; on this testimony, therefore, Rabbi permitted the entire territory of Beit She’an. Thereupon his brothers and other members of his father's family combined to protest, saying: The place which was regarded as subject to tithes by your parents and ancestors will you regard as free? Rabbi, thereupon, expounded to them the following verse: … so in my case, my ancestors left room for me to distinguish myself. … as the statement of R. Simeon b. Eliakim who reported R. Eleazar b. Pedat in the name of R. Eleazar b. Shammu'a [as follows]: Many cities which were conquered by the Israelites who came up from Egypt were not reconquered by those who came up from Babylon, for he held the view that the consecration of the Holy Land on the first occasion [by Yehoshua] consecrated it for the time being but not for the future. They therefore did not annex these cities in order that the poor might have sustenance therefrom in the Seventh Year.

(B Chullin 6b-7a)

The Halachic Status of Beit She’an vis-à-vis Terumot and Ma’aserot

Beit She’an is mentioned here as a city that was conquered in the conquest of the Jews who left Egypt (olei Mitzrayim), but not those who left Babylon (olei Bavel), which makes it exempt from the mitzvot associated with the Land of Israel. For instance, (according to Rashi) it is exempt from the laws of shemita and during this year the poor could go there and receive ma’aser ani (poor man's tithe). There is a major disagreement among the Rishonim as to the precise nature of the exemption Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi made for Beit She’an. Rashi and the Ra’avad believe that he exempted vegetables, since the prerogative to separate from them terumot and ma’aserot is only rabbinic—but grain, wine, and oil must all be tithed since Rebbe would not annul a biblical obligation. Rabbeinu Tam argues that the exemption here only relates to demay, when it is not certain whether produce was tithed, but when there is no doubt in its status (tevel vaday), even vegetables must be tithed. The Smag and Rabbi Yosef Karo (there are some who understand this to be the opinion of the Rambam as well) believe that Rebbe exempted Bet She’an completely from the obligation of tithing, even from tevel vaday, as well as all the places that were not conquered by Olei Bavel. Others (Ramban and Rashba) understand the Rambam to have ruled that only Beit She’an (and similar areas) were completely exempted by Rebbe from terumot and ma’aserot since Jews did not live there at that time and it was far from the concentrations of Jewish settlement in his time.

Rabbi Ishtori Haparchi, who traveled to settle in Beit She’an during the later Middle Ages, reports in his book Kaftor va-Ferach that the custom of Beit She’an in his time was to set aside terumot and ma’aserot from all produce but without a beracha. The Chazon Ish rules that Rebbe’s leniency for Beit She’an might be valid in the historic Beit She’an itself, but not in its environs, so the Beit She’an Valley is not included in this exemption. For this reason, Rabbi Shlomo Rosenfeld wanted to obligate the Beit She’an Valley (which stands out in its cutting-edge Jewishly-grown agriculture) in taking terumot and ma’aserot with a blessing, but Rabbi Yehuda HaLevy Amichay and Rabbi Ehud Ahituv believe that since there is doubt in the matter, tithes should be taken without a beracha.

Beit She’an: the City

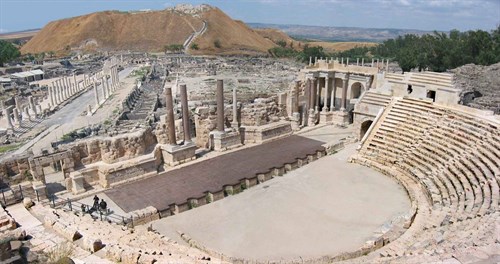

Beit She'an National Park

Beit She’an is one of the most ancient cities in the Land of Israel. Tel Beit She’an is where it all began—this was the location of Egypt’s headquarters for its rule over the Land of Israel prior to Yehoshua’s conquest of the country. About Beit She’an, situated in the portion of the tribe of Menashe, it is stated that its original inhabitants stayed on after the Israelite conquest since they had iron chariots (ancient tanks); when the Jews finally overpowered them, the Cana’anites paid them taxes. Following the death of King Saul and his sons in the adjoining Gilboa, the Philistines hung their corpses on the walls of the city, from where the inhabitants of Yavesh Gilad took them to give them a decent burial. It seems that King David conquered Beit She’an, and King Solomon stationed a governor there.

In Second Temple Times, Beit She’an was one of the leading cities of the Decapolis (deca=ten, polis=city), a loose confederation of ten cities and the only one of them located west of the Jordan River. It was a mixed city, whose Jewish inhabitants (known not to speak punctilious Hebrew) called “Beishan,” while the gentiles called it Scythopolis. The remains of the city can be seen today in the National Park there. The remains are chiefly of the large Roman and Byzantine cities. The city was in no way the symbol of coexistence, since during the Great Rebellion its Jewish inhabitants were murdered by their neighbors. The city was destroyed in an earthquake in 8 CE, and then it became a small Arab settlement. It was so at least during the periods Jews came to settle there, such as Rabbi Ishtori, who settled there in 14 CE. During the War of Independence, the Arabs of Bison deserted the area and a Jewish town was reestablished there and called Beit She’an (which now has become a city), populated by immigrants from Arab countries. Today the city’s population numbers some 17,000 residents.

Beit She’an is blessed with a thriving agriculture due to the combination of heat, fertile soil, and plentiful water. Reish Lakish noted that if Gan Eden is located in the Land of Israel, Beit She’an would be its entrance.