Parashat Vayetze: Ma'aser, a Symbol of Permanence

About Ya'akov Avinu, who instituted giving ma'aser for generations by personal example, and the principle behind ma'aser verses teruma. The dispute about the name "shum ba'al bachi" among the interpreters of the Mishna, and on the role of Ba'albek (Lebanon), past and present.

"אם יהיה א-לוקים עימדי... וכל אשר תיתן לי עשר אעשרנו לך" "If G-d remains with me … and of all that You give me, I will set aside a tithe for you." (Bereishit 28:20-22)

A Tenth of Everything

Ya'akov Avinu is not the first person in the Torah who uses the term ma'aser; Avraham (then Avram) did so before him; in parashat Lech Lecha he gives a tenth of the war spoils to Malki Tzedek, king of Shalem, priest to G-d on High. However, there is a novelty here: by Avraham we see tithing as a one-time occurrence; Ya'akov, on the other hand, commits himself to tithing on a regular basis. It is not for naught that the Ba'alei HaTosafot in their commentary on the Torah cite the midrash that this is the source of ma'aser kesafim, since the biblical obligation for ma'aser is stated with regard to animals and produce alone (the major branches of livelihood in those times), with no mention of other forms of monetary profit. It is interesting to note that Yaakov Avinu does not make an amorphous promise about the amount he will give; rather he feels it important to set a fixed rate—which actually isn't so high (those in the middle class often pay much higher rates of income tax), but is also not at all marginal in terms of one's regular cash flow.

Our Sages (Bereishit Raba 70:7) understand that this tithe is not necessarily limited to monetary profit, but rather refers to one-tenth of anything G-d blesses him with, including children. The tribe of Levi is one out of the ten sons who is consecrated for service in the Beit Hamikdash (the Midrash discusses why only one son out of everyone is dedicated as a tithe). This fact teaches us that Yaakov's pledge goes beyond a specific, one-time commitment made in a time of crisis, but rather is a general approach in the service of G-d.

Regular Service of G-d: The Key to Genuine Holiness

There are times when we feel a major awakening to serve G-d—desiring to reach lofty heights in prayer, throwing ourselves into intense Torah study, or donating a large sum of money to charity. All of this is wonderful, but on its own is insufficient to transform us into a vessel for the resting of the Divine Presence. To truly become a receptacle for sanctity, we need to adopt a way of life where in any given situation and in any emotional state we will be connected to G-d—not only at rare moments of spiritual arousal. Ma'aser is the classic example of this. When we make sure to set aside at least a tenth of our resources that G-d puts at our disposal, and we return them to Him, we remain constantly connected. Of course, if we want to donate even more, we can and that is wonderful (while there are upper limits to this as well, and we may not donate more than one-fifth to charity), but the minimum that binds us to G-d is a constant, and we are to give this amount no matter what.

Ma'aser and Teruma: Two Types of Divine Service

It is interesting to note that there are two types of gifts we are supposed to give from our produce. There is the teruma gedola, given to the Kohen, for which the Torah did not set a specific rate – neither an upper or lower limit (only that the entire granary should not be dedicated as teruma); even one stalk of wheat is enough to cover all of the produce. While the Sages institutionalized the framework for giving teruma to a greater degree, they still left room for personal choice, and offered several options for teruma: 1/40th (ayin tova, generous), 1/50th (ayin beinonit, standard), and 1/60th (ayin ra'a, stingy). Moreover, apparently to preserve the original spirit of teruma, even after fixing rates, the Sages instituted that teruma be given only as an estimate, not as an exact measurement (Mishna Terumot 1:7).

As opposed to the teruma gedola, there is the ma'aser given to a Levi, including the terumat ma'aser, the tenth-of-the-tenth that the Levi gives to the Kohen. Here we have a fixed rate, which may not be set aside based on a rough estimate, but rather based on a precise calculation ("do not frequently tithe by estimation," Avot 1:16). This is the same type of ma'aser that Ya'akov Avinu is talking about—which expresses this fundamental element in the service of G-d. While not extraordinary, tithing on a regular basis acts to preserve and renew the force of giving and permanently binds us to G-d.

Garlic from Ba'alabek

"שום בעל בכי ובצל של רכפה.. פטורין מן המעשרות ונלקחין מכל אדם בשביעית"

"Garlic of ba'al bechi, onions from Rikhpa … are exempt from tithes and may be bought from any person during the Sabbatical year" (Mishna Ma'aserot, 5:8)

Rambam: Garlic that Makes You Cry

Rambam explains that the term ba'al bechi is an adjective describing the garlic's extreme spiciness, which causes tearing, and due to this excessive spiciness it is not generally eaten. According to the Rambam's line of thought, the reason to exempt this variety of garlic, along with the other items on the list in the Mishna, is the fact that they only grow in the wild, as ownerless (hefker), and thus are exempt from terumot and ma'aserot. It is possible to buy such garlic, along with the other items, from anyone during the shemita year, even from those who are not known to be meticulous about their halachic observance. This would not constitute the prohibition of giving shevi'it money to an am ha'aretz. The Sages prohibited giving money imbued with shemita sanctity (after food sacred with the sanctity of shemita is purchased, the money used to purchase it also become sacred, termed kedushat shevi'it) to an am ha'aretz (ignoramus vis-à-vis halacha), since he might use the money for purposes other than purchasing food (Perush Hamishna LeRambam, Shevi'it 9:1) Rabbi Yosef Kapach learns from this that garlic ba'al bechi is subject to ma'aserot, according to the Rambam, despite the fact that it is inedible. The only reason it is exempt in this case is because is it is ownerless, since even an inedible spice is subject to ma'aserot if it is cultivated, as opposed to growing wild.

The Rash: Ba'al Bechi is a Location

The Rash (Rabbi Simshon ben Abraham of Sens) believes the reason for the garlic's exemption and the other items on the list has to do with something else completely: they are from outside of the Land of Israel. Of course, all produce from outside of Israel is exempt from ma'aser and any prohibitions related to the shemita year. According to the Rash, even though at a certain point the Sages did obligate ma'aserot from produce grown countries adjacent to the Land of Israel abroad when similar produce was grown in the Land of Israel, the vegetables mentioned in the Mishna did not have Israeli counterparts (the ba'al bechi garlic was different than the garlic grown in the Land of Israel). The Rash offers an additional explanation to that brought by the Rambam (which he also cites) to the name ba'al bechi: it is the name of a location. Rabbi Ovadia of Bartenura expands on this, and adds that it is a place in Lebanon. Rabbi Pinchas Kehati, in his gloss on the Mishna, explains that this is a reference to the city of Ba'albek in the Lebanese Valley.

Ba'albek, Lebanon

Identifying ba'al bechi as Ba'albek can be somewhat problematic, as the verse in Yehoshua (11:17) states that the edge of the boundary of Yehoshua's conquest was Ba'al Gad in the Lebanese Valley; Ba'al Gad is identified with modern-day Ba'albek (among others possibilities). What this means is that garlic from Ba'albek actually grown within the boundaries of olei Mitzrayim, a region that is generally subject to terumot and ma'aserot, even if only due to the enactment of the Sages. How then can the Rash define the area as outside of the Land of Israel and exempt from terumot and ma'aserot? It seems, then, that the Rash holds that not every place in the olei Mitzrayim region is subject to terumot and ma'aserot. Only areas closer to the olei Bavel boundaries, which have an added measure of sanctity, are subject to terumot and ma'aserot, while areas farther away from these boundaries are exempt. The definitions of "close" and "far" are not sufficiently clear. It could be that Ba'albek, situated deep in modern-day Lebanon, is considered "far" from the boundaries of olei Bavel (or simply is not connected to the Land of Israel), which is why it is completely exempt from terumot and ma'aserot. (About terumot and ma'aserot in the boundaries of olei Mitzrayim, see the article by Rabbi Yehuda Amichay in Emunat Itecha 32, 5760, pp. 36-43).

From the Center of Ba'al Worship to a Hizballah Stronghold

Ba'albek is the capital of the al-Beqa'a region (the Beqa'a Valley, the Lebanese Valley), and it is situated in the north of this region. The Lebanese Valley is the Lebanese version of the Syrian-African fault line, which continues onto the Hula Valley. The fact that it serves as a Hizballah stronghold and a hub for hashish dealers provides an added, current significance for the moniker ba'al bechi.

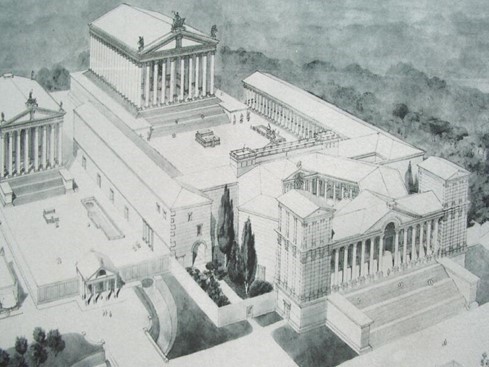

The name Ba'albek means "master of the valley," and it refers to the Canaanite god ba'al, worshipped by Phoenicians, the city's ancient inhabitants. During the Hellenistic era, the city's name was changed to Heliopolis (=city of the sun), also as a reference to the sun god, in its different variations. The idol worship in the area came to an all-time high during the Roman era, when several temples were erected, this time to Roman deities.

Starting in the Middle Ages, when the pagan function of the city had ended, we hear about Jews settling the area. Among the disciples of Rabbi Sa'adia Gaon, there were those who settled in Ba'albek. Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela, who visited the city in 1175, describes the city as a resort town for the important communities in the area, including Damascus. In the 19th century the city was home to several Sephardi Jews.

Ba'albek, whose population is approximately 31,000 today (2018) (the majority of whom are Shi'ites), serves as the home front for the Hizballah. The area also features a hospital, which serves the terror organization. In the summer of 5766 (2006), during the Second Lebanon War, IDF forces attacked the city. Soldiers from elite units penetrated the hospital to find a senior Hizballah official; the official was not found, however several other Hizballah officers were captured. A soldier from a commando unit, lieutenant colonel Emmanuel Yehuda Moreno, was killed during the clashes in the Baalbek region during this war.