Parashat Nitzavim: Rosh Hashana for an uplifted nature

The first day of Nissan and the first day of Tishrei represent two directions in Judaism: one of Divine rectification and one of natural rectification. On Rosh Hashana we are supposed to examine ourselves and be examined regarding whether we indeed progressed and helped others move ahead, or whether we sunk ourselves further into the natural, pagan world, a world that cannot hope for anything better.

Rosh Hashana for an uplifted nature

The four new years are: the first of Nisan, the new year for the kings and for the festivals; the first of Elul, the new year for the tithing of animals; Rabbi Eliezer and Rabbi Shimon say: the first of Tishrei. On the first of Tishrei, the new year for years, for the Sabbatical years and for the Jubilee years and for the planting and for the vegetables; the first of Shevat, the new year for the trees. These are the words of the House of Shamai; The House of Hillel says, on the fifteenth thereof. (Mishna Rosh Hashana 1:1)

The fact that the year is cyclical and continuously repeats itself makes it possible for people to cite its beginning at various possible points. The new year of one religion falls out on one date, while another religion marks it on a different date. One can assume that behind the demarcation of the beginning (and end) of the year is also an ethical message, which can be agreed or disagreed with. It seems that the strangest of them all is the Jewish New Year. Strange simply because there isn’t just one of them. The Mishna counts four (!) new years, whereas each one serves as the new year for a different area. We could make do with individual explanations for each one of these new years; however, since the decision of when to begin the year bears significance, it seems that local explanations will not suffice.

While two of the four new years (the first of Elul and either the first or the fifteenth of Shevat) are purely functional, we will focus on the more prominent new years—the first of Nissan and the first of Tishrei. The latter is referred to as simply “Rosh Hashana” throughout the Oral Torah, which is how we refer to and view it until today.

Nature and above nature

The natural New Year, the one symbolizing the start of the agricultural season, is that of Tishrei. While the first of Nissan marks the beginning of a new stage, when the world shakes off its winter slumber and returns to life, still it is not the beginning of something new. At most, it is the manifestation of the life forces that had remained latent up until then.

If we take a deeper look, we will see that the new year of Nissan is truly a starting point for things not rooted in nature—things that are not universal but rather are unique to the Jewish People. The first of Nissan is the New Year for counting the years of Jewish kings (as is the majority opinion in the gemara). It also is the first of Jewish festivals, whose date is determined by the Jewish People “Who sanctifies Israel and the times—Israel who sanctifies the times”; had we not received the Torah, none of these festivals would have existed (instead there would be agricultural holidays with completely different content).

In contrast, a quick look at the areas for which the first of Tishrei is their new year shows that they are connected to the natural and the universal: years (“the age of the world”, Rambam), and various mitzvot associated with the agricultural world. These include the shemita years, the yovel year (marking the start of the sanctity of these years), planting (a tree planted 44 days before Rosh Hashana will begin its second year on the first of Tishrei with regard to its year of orlah) and for vegetables (it is prohibited to set aside ma’aser from vegetables harvested before the first of Tishrei to exempt vegetables harvested after that date. Also, some of the ma’aserot change from year to year: ma’aser sheni must be taken on years 1,2,4, and 5 of the shemita cycle, while ma’aser ani, the poor tithe, on years 3 and 6).

Idolatry vs. the light of Moshiach

The ancient pagan outlook was that what was in the past is what will be in the future; the year and the entire world is a repetitive cycle that cannot be broken, and that one should not hope for anything better. Winter will be followed by spring, and after the summer, autumn will come, and this cycle will repeat itself over and over ad infinitum. Judaism gave the world a whole new message: the world advances, it continues to move ahead and ascent until the coming of the Redemption, when Moshiach will reveal his light. This idea spread to other religions as well, which, albeit, distorted the original Jewish message, but they took with them the hope for a brighter future—to the point that the messianic idea has become a fundamental belief of the majority of the world population.

It has gotten to the point that even sworn atheists have adopted this messianic idea, at times in an even more extreme fashion than have believers. Want proof? Communism and humanism are two. Furthermore, if we look at the natural sciences, even Darwin’s Theory of Evolution, which serves as the cornerstone of every movement that wants to deny the creation of the world by G-d as detailed in the Torah (the theory is not necessarily inconsistent with what is written there, but this is not the forum to cover this issue in depth) is based on the idea of development and advancement in the most rigid of spheres: the natural world (see more about this idea in Orot HaKodesh part 2, p. 537).

The novelty in the original Jewish approach is that the change will come from within nature, but with Divine assistance. It is insufficient to believe that one day we will emerge from the quagmire of this bleak and dismal existence; rather, our G-d-given duty is to uplift and sanctify our lives within their natural framework. This holds true for the natural world, where the Divine directive to rectify the world lay in the mitzvot associated with the Land of Israel, and is true for any other system in our lives. History, historiya in modern-day Hebrew, is not only a description of the random events that took place in the world, but rather the hester-y-a—G-d’s hidden hand, as it were, that guides His creation towards rectification.

The Rosh Hashana spiral

The basis for the change that undermines natural systems in the form of a straight line that keeps ascending, is laid by the month of Nissan—the month we left Egypt amid blatant miracles; on the other hand, the natural, cyclical basis is laid by Tishrei, the month the world was created (according to the opinion of R’ Eliezer, whose opinion was accepted and applied in the Rosh Hashana liturgy: “This is the day Your works began”). However, here this is not a circle that repeats itself in a loop, rather a spiral, whereas each year we return to the same spot, only higher. The Jewish New Year is not a mere historical landmark, but rather the hester-y-a that shows the advancement of the world yet another stage.

When the People of Israel were not in its land it could rectify the world within nature, which is why the New Year mentioned in the written Torah, given in the desert (while its becoming the first of all months was determine while they were still in Egypt), is the first of Nissan. The Oral Torah, on the other hand, with its fundamental texts, Midrash Halacha and the Mishna, were composed in the Land of Israel, and these texts cite the first of Tishrei as the New Year.

The second mishna of tractate Rosh Hashana cites an additional event that occurs on the first of Tishrei: “All inhabitants of the world pass before Him as benei maron.” That is, on this day all creations are scrutinized, and G-d assesses whether they have progressed, or if they have remained in the same place they were last year, and the only thing that has changed is the location within the circle that truly has no beginning and no end.

Wishing everyone a good and sweet New Year, a year where we will merit to progress and advance the entire world towards its eternal destiny!

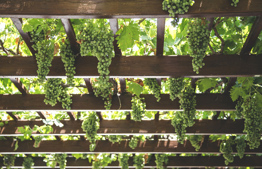

Kerem revay in Elonei Mamre

Kerem revay was brought to Jerusalem from a radius of a day-long journey. And what is its boundary? From Eilat in the south […]

(Mishna Ma’aser Sheni, 5:2)

Where is “Eilat in the south”?

We are now at the close of the shemita year, which is exempt from terumot and ma’aserot, and about to begin the first year of the shemita cycle in which we set aside ma’aser sheni, along with the teruma gedola and ma’aser rishon (and not ma’aser ani, taken on years 3 and 6 of the shemita cycle). As such, we should return to this mishna that we had visited in the past. The Mishna mentions that its kerem revay (as well as ma’aser sheni) must be brought to Jerusalem and not redeemed on money, as it was in relatively close proximity. The goal was that the market places of Jerusalem would be decked out in fruit. A place in “close proximity” to Jerusalem was a location that was a distance of one day’s journey on foot. The southernmost border in this radius was “Eilat.”

Obviously this could not possibly be the Eilat that we know today, the city located on the shores of the Red Sea, in Israel’s most southern border, since walking distance to Jerusalem from there exceeds one day by far. Rather, we must search for the mishnaic Eilat in the hills of Hebron, located south of Jerusalem. This area boasts many vineyards, renowned for their excellent quality (thanks to the altitude and its cool air that is positively affects the quality of the wine produced from the grapes). The proposed location is referred to in Arabic as Ramat al-Khalil (Ramat Avraham), north of Hebron and 32 km south of Jerusalem—which makes it possible to travel by foot to Jerusalem in a day’s time.

Avraham Avinu, pistachio, Jewish slaves, and the Hebron Agreement

The name Eilat comes from the root elah, meaning pistacia, a name similar to Elonei Mamre, in Hebron (Josephus Flavius confuses between elah, the pistacia and alon, the oak tree). The area is also called Botna, after the renowned Syrian pistachio tree, referred to as boten (the peanuts that grow in the ground, boten in Hebrew, was not at all known in ancient times; it is a discovery of the new world). St. Jerome, Doctor of the Latin Church, records that at the famous slave market at Botna thousands of Jews were sold into slavery following the failure of the Bar Kochva rebellion, which is why the place is infamous. It was also a prominent place of idolatry, and it was forbidden to make use of the trees.

Until the mid-nineteenth century, Elonei Mamre boasted an impressive tree called eshel Avraham, recorded in tradition as the tree the angels leaned against when visiting Avraham Avinu. From the end of the nineteenth century, the tree was identified in a different location—in the courtyard of the Russian church in Hebron. The Israeli government did not see the merit of Avraham Avinu and the suffering of the many Jews in this area in the days of the Romans as adequate justification to insist on holding the territory; Elonei Mamrei was handed over to the Arabs in the 1997 Hebron Agreement, with the promise that free access would be allowed to the Jews, a promise that was not kept.

During our prayers in the High Holidays, when we mention the merit of Avraham Avinu, let us remember the places where he lived and acted, areas unfortunately not under our full sovereignty. Let us also remember the mitzva of ma’aser sheni that we cannot fulfill in its entirety today, as well as other mitzvot associated with ritual purity and impurity, Jerusalem, and the Beit Hamikdash.