Parashat Teruma: the encounter between two types of sanctity

About the Temple the Jewish People are commanded to build and its location today (as opposed to when it was not linked to a specific location). The relationship between the sanctity of the Beit Hamikdash and that of the Land of Israel, and the link to the mitzva of bikurim.

"Make for me a Sanctuary and I will dwell within your midst" (Shemot 25:8).

From mobility to permanence

The heading above should look strange to anyone who has been following Jewish history in the Land of Israel over the past century. Everyone knows that the Beit Hamikdash is supposed to be in a very specific location. The Beit Hamikdash could not be situated in any city—or even moved a meter in any direction! Ever since the mufti of Jerusalem Haj Amin al-Husseini incited Arabs to attack the Jews in the Arab Uprising of 5689 (1936), through the recent Al Aqsa Intifada, the Jewish-Arab conflict in Israel can be boiled down to several hundred square meters on Temple Mount. Yet here in our parasha the Jewish People are in the desert and are commanded to erect a temple. Not just any temple, but a Mishkan, a mobile temple, one that can be here one day and there another. What's going on here? Why could the Mishkan be a mobile structure, while the Beit Hamikdash had to be situated at a very specific location?

In attempt to understand this, we will take a look at two main sources. The first discusses that change in status of the Mishkan throughout the generations, while the second deals with the sanctity of the Mishkan's location. The Mishna (Zevachim 14,4-8) gives us a brief historical survey of the Mishkan in the Land of Israel. The main point of the Mishna here is to ascertain when bamot were permitted. At certain times when the Mishkan was standing, it was permitted to bring certain sacrifices on bamot—the name for an altar outside of the Mishkan—while at other times this was forbidden. During three periods, bamot were forbidden: in the desert from the time the Mishkan was established through entry to the Land of Israel and encampment at Gilgal; during the 369 years the Mishkan stood at Shilo; and since the building of the Beit Hamikdash in King Solomon's time. Before this time, and during the intermediary periods, bamot were permitted.

The source for the prohibition of bamot in Shilo and Jerusalem is the verse: "because you have not yet come to the resting place [menucha] or to the heritage [nachala]" (Devarim 12:9); the Mishna explains menucha as a reference to Shilo and nachala as a reference to Jerusalem. The term menucha describes a temporary period of sanctity resting in one area for several hundred years, but not because this is its destined place. In contrast, Jerusalem is nachala because of the "fixed nature of its sanctity and its eternal existence." (Peirush Hamishna, Rambam Zevachim 14:8).

Who determines sanctity: G-d or the Jewish People?

Indeed, the sanctity of the location of the Beit Hamikdash lasts forever, even after its destruction. Rambam (Hilchot Beit Habechira 6:14-16) stresses that the sanctity of the Beit Hamikdash (in the context of the mitzvot tied to it) differs from the sanctity of the Land of Israel (vis-a-vis shemita, ma'aserot, etc.). While the sanctity of the Beit Hamikdash stems from the "Divine Presence, which is never nullified," the obligation of the Land of Israel in "the Sabbatical year and tithes is not due to its being conquered by many [Joshua and olei Mitzrayim]. When the Land was wrested from [the Jews'] hands, the conquest was voided and it was exempt from a biblical obligation of tithes and the Sabbatical year, since it is not [considered] the Land of Israel." Later on, parts of the Land are sanctified in early Second Temple times (olei Bavel). Since this was not accomplished through a military conquest, but rather civilian settlement, this sanctity persists even later on. According to these sources, it would seem that the Mishkan becomes sacred due to the Divine Presence, while the Jewish People are the ones who sanctify the Land of Israel.

The place that will be chosen … by the Jewish People?

However, this too is not so simple. My rabbi and teacher, Rabbi Shmuel Tal, noted that nowhere in Tanach do we see King David receiving a prophecy regarding the exact location the Beit Hamikdash should be built. There are various traditions brought down by our Sages that it was the Jewish People who decided that the "place that G-d will choose" is Temple Mount, in Jerusalem—and implemented by Kind David. This is in contrast to other decisions made based on prophecy or consultation with the urim ve-tumim, which were far less consequential to the Jews' future. On the other hand, it is clear that with all due respect to the Jews' conquest and settlement of the Land of Israel, had we conquered or settled in Uganda, the mitzvot tied to the Land of Israel would not apply.

Similarities and differences

It seems we can explain this as follows: the same fundamental principle, which is also a basic tenet of Judaism, holds true for both types of sanctity. Sanctity is the product of a joint effort, of both G-d and the Jewish People. Redemption cannot arrive without both partners contributing their share. It's not that G-d can’t save us on His own, it's just that this is the whole purpose of the world's creation: so that human beings will take an active part in rectifying the world (as the Ramchal explains at length in Da'at Tevunot). Yet, these are still two separate systems. The Beit Hamikdash is mostly G-dly; it is the main pipeline that brings down all G-dly abundance to the world. Our ability to make an impact is only on a very low level, with physical (but vital!) vessels, that receive this abundance. However, working the Land of Israel's soil is primarily physical, while G-d's blessing, though critical, is hidden.

As this is the case, the sanctity of the Beit Hamikdash could technically rest anywhere, since G-d's glory fills up the entire world. However, the point of connection between heaven and earth can only be formed when the Jewish People—G-d's representatives in the world—identify the place and erect the Beit Hamikdash there. In contrast, the Land of Israel's sanctity cannot just appear like the Mishkan, in any place, since here the contribution of the Jewish People—who can only fully fulfill their role in the Land of Israel—is much more apparent and central.

Note that in this context, that there is a dispute between two groups of great Torah scholars in our generation (and we will be careful not to take sides here) regarding the level of involvement we need to have in making concerted efforts to visit Temple Mount and take action to build the Beit Hamikdash. Both schools of thought based themselves on the Rambam's ruling that the sanctity of the site of the Beit Hamikdash is eternal. There are some scholars who staunchly support making concerted efforts to settle Israel and strengthen our hold on it, but refrain from taking action on behalf of Temple Mount, and are staunchly opposed to visiting the site. They emphasize what we said here, that when it comes to the Beit Hamikdash, the main component is G-dliness, as opposed to the sanctity of the Land of Israel. Other great Torah scholars, in contrast, maintain that while the sanctity of the Beit Hamikdash stems mainly from G-d, for this sanctity to be reveled once again the Jewish People need to make an effort as well, as was the case when the site was first sanctified in the times of David and Solomon.

The encounter between heaven and earth next to the altar

"You shall make the altar of acacia wood …" (Shemot 27:1)

"Once one gets to 'My father was a wandering Aramean,' one takes the basket off one's shoulder and holds it by one's lip. The priest places his hand under it and waves it. He then recites from 'My father was a wandering Aramean' until finishing the entire passage and rests [the basket] beside the altar and prostrates and leaves." (Mishna Bikurim 3:6)

The mishna above describes the final stage of the mitzvah of bikurim, bringing first fruits, the climax, where the one bringing the bikurim reads out the bikurim text (provided that it is one's own bikurim and that it is the time of year when the text is recited), which we all are intimately familiar with from Seder night, as it is the basis of Magid. Upon completing this recitation, the bikurim bearer places the basket on the southwest side (closer to the Sanctuary and the Holy of Holies), and leaves. It seems that this is the closest area that non-Kohanim could come to (while there are some opinions that during the time of encircling the altar on Sukkot, Israelites would also participate in the hakafot, so there were other opportunities for Israelites to be there as well; see the discussion in Machzor Hamikdash for Sukkot, pp. 45-47). This is also the most sacred point where there is a connection to the mitzvot tied to the Land of Israel, where this extremely powerful bond forms between these two sanctities we addressed above: the sanctity of the Land of Israel and the sanctity of the Beit Hamikdash. To our great sorrow, we can no longer observe this beautiful mitzvah of bikurim today, since (in contrast to other mitzvot tied to the Land), it depends on the existence of the Beit Hamikdash (Mishna Shekalim 8,8).

The Western Wall of the Azara

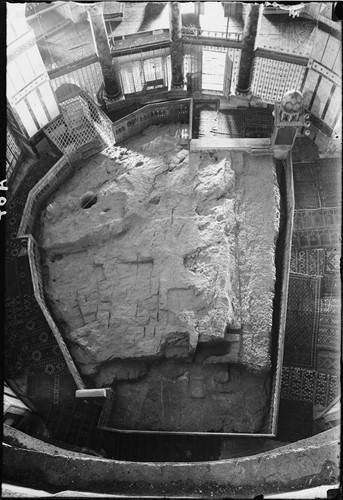

The altar discussed in our mishna is the mizbe'ach hachitzon, the "outer altar," in the azara, the Priestly Courtyard. Rabbi Zaman Koren, in his book Ve'asu Li Mikdash, attempts to identify the azara. He proves from the words of Chazal that the walls of the azara were perfectly aligned with the four directions of the wind, so that the eastern wall (where the famous Nikanor Gate was), for instance, was precisely in the East. The walls surrounding Temple Mount today (one of them being the Western Wall, the Kotel) are not aligned in this manner. The eastern wall deviates six degrees from the true East, while the western wall deviates ten degrees from the true West. However, the eastern wall of the rama, the elevated area on Temple Mount where the Dome of the Rock stands today (where most traditions hold is the site of the Foundation Stone), deviates from the East by one degree alone.

Furthermore, Rabbi Koren notes that during Cheshvan 5731 (1970), archeologist Dr. Ze'ev Yavin visited Temple Mount when Muslims were involved in demolition work there east of the northern section of the elevated eastern wall. There he noticed an ancient wall 2.5 meters east of the rama wall. When he returned to the site to take a picture of his discovery, it had already been demolished. Stones were strewn all around the area. Only one stone (which might have been chiseled off the original stone) was still in place. Since the southern side of the eastern rama wall is more ancient than its northern side, we can assume that the original wall continued on little more to the east (perhaps it was the remnants of this wall that Yavin discovered). This created a parallel wall to the true East, and this was the eastern wall of the azara. Rabbi Koren asserts that since we know the distance in amot between the kodesh kodashim and the eastern wall of the azara, we can use this finding to ascertain the exact length of an ama, which he believed was approximately 57.4 cm. In this way, we can also identify the exact spot of the altar.

Foundation Stone