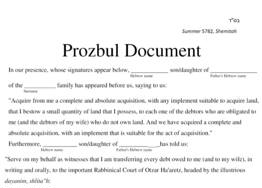

Loan Remission for Bank Deposits

What happens if a prozbul is not written for a bank account? Will it still be permitted to draw from the account?

Nowadays many have the practice of writing a prozbul, even when they have not formally lent money, to ensure their ability to withdraw money deposited in bank accounts post-shemitat kesafim (debt remission at the end of the shemittah year). However, in my opinion, this is unnecessary since money deposited in banks is not annulled even in the absence of a prozbul, as explained below. Therefore, even post facto, there is no problem to draw money from bank accounts for those who did not write a prozbul. But I will not rule this way practically until receiving approval from other rabbis on this matter.

We must first discuss the status of commercial banks. As corporations, do they have the status of individual borrowers, whose debts must be annulled by lenders? Or perhaps, since corporations are not individual people, their lenders need not annul existing loans? One must also relate to banks’ standing as Jew or non-Jew. Does the religious status of stockholders determine corporate identity, or is it based on worker or manager status? I will assume that for a bank whose managers, workers, and stockholders are Jewish, there is a fundamental requirement for shemittat kesafim, with lenders required to annul existing debts.

It is forbidden to collect on debts requiring annulment. Even if the borrower desires to pay, one must respond “I remit it.”[1] One is only permitted to accept payment if the borrower nonetheless insists on paying. Therefore, it would appear forbidden for a lender to collect on his debts after shemittah, unless he had previously notified the borrower of his intentions to annul with the borrower subsequently renouncing the annulment. So, if bank deposits were considered to be debts annulled at the end of shemittah, it would be forbidden to draw from those accounts in the absence of a prozbul. There are those who claim that since banks are closed at the beginning of the eighth year, we relate to all pay-off dates as set to after shemittah. However, this seems forced. Would they limit the applicability of shemittat kesafim to the very specific case of one who keeps his business open and does not attend synagogue on Rosh Hashanah? The reasoning for leniency must come from elsewhere.

There are two types of bank deposits. There checking accounts, which generally do not make profits but allow for impromptu depositor withdrawals. Then there are deposits with limits on depositor withdrawals until the end of a defined period, but they accumulate profits. To avoid the prohibition of ribbit - interest, as per rabbinic requirements, banks in Israel utilize a general heter iska (lit. permissible transaction). Under the iska, all the money a bank is responsible to pay interest for is categorized as funds given for a venture. Essentially, according to the iska arrangement, money given to banks is split into two distinct components, with one half defined as a loan (halva'ah) and the other as assets deposited for safekeeping (known as a pikadon; here we will refer to it as a deposit). The Acharonim disagreed about how the law of shemittat kesafim applies to the components of the heter iska. According to the Shulchan Aruch,[2] the loan half of the iska is annulled, while the deposit is not. But the Ketzot HaChoshen holds that the laws of shemittat kesafim do not apply to the loan half of the iska because the entire iska is treated as a deposit, with the entire deposit not annulled.[3] Nonetheless, according to both opinions, the deposit part is not annulled, since only loans are canceled during shemittah.[4] Accordingly, there is disagreement whether after shemittat kesafim one can withdraw half or the entirety of bank deposits with iska status.

The machloket between the Shulchan Aruch and Ketzot HaChoshen is not relevant to checking accounts, which do not accrue interest, since they do not have the status of iska. However, it remains to be determined whether these accounts have the status of a loan or deposit. It is significant that it is referred to as a deposit and not a loan. While banks have absolute responsibility for deposited funds even in instances of disaster, similar to the responsibility of a borrower, this is not decisive. We find that there are safety deposits that carry complete responsibility on the part of the custodian, and they do not lose their safety deposit status. For example, when one deposits unmarked money with a money changer, the latter is permitted to use the money while assuming complete responsibility for the money, without a transformation of the money into a loan.[5] As the Rema notes, depending on the circumstances, the money changer may or may not have to repay profits to the depositor.[6] The fact that he is not prohibited from doing so proves once again that we are not dealing with a loan, which would induce a prohibition of interest. (It is true that even for safety deposits it is prohibited to prospectively agree to assume responsibility and repay partial profits. However, this is due to a specific aspect of the arrangement, in which the investor is “close to profit and far from loss” [see Bava Metzia 70a]. However, from the above-mentioned laws it is clear that there is a difference between loans and deposits even when there is absolute responsibility).

The difference between a deposit and a loan lies in the fact that loans primarily benefit the borrower while a deposit primarily benefits the depositor. Therefore, a loan has fixed times, with the lender prohibited from demanding repayment prior to the pay date. In contrast, a depositor is permitted to spontaneously demand the return of their deposit, even when the custodian (who assumed responsibility) is permitted to use it. Similarly, placing money in checking accounts is done for the benefit of the depositor, who is looking for a safe place to keep their money, amongst other reasons. If so, checking accounts have the same deposit status as the previously mentioned case involving the money changer.

Based on the above, where we find cases similar to loans in their characteristic assumption of responsibility but nonetheless carry the status of a deposit, we can bring support for the position of the Ketzot HaChoshen regarding the loan half of an iska agreement. But this is beyond the scope of this article.

To summarize, there is no shemittat kesafim when it comes to checking accounts without interest while there is disagreement regarding half of the sum in checking accounts with interest. But perhaps there is another explanation which will remove the prohibition shemittat kesafim for all types of checking accounts. Parties to a regular loan that stands to be annulled during shemittah can include conditions which effectively avoid annulment.[7] According to the Rema, basing himself on Maharik, when the parties designate the loan using the terminology of a deposit, they have effectively avoided annulment, since safety deposits are never annulled by shemittat kesafim. Therefore, even if one were not to accept the definition of checking accounts as deposits, the very fact they are called “deposit accounts” is enough to remove the halachah of shemittat kesafim from them. And this would equally apply to checking accounts that accrue profits.

In conclusion, any account designated as a “deposit account” is not annulled even without a prozbul.

Translator: Ephraim Fruchter

For the Hebrew Article.

[1] Mishnah Shevi’it 10:8

[2] Aruch HaShulchan, Choshen Mishpat 67;3.

[3] Ketzot HaChoshen, Choshen Mishpat 67;2.

[4] See Shulchan Aruch, Choshen Mishpat 67:4,6 as well as Be’ur HaGra, Choshen Mishpat 67;18.

[5] Shulchan Aruch, Choshen Mishpat 292:7

[6] Sema, Choshen Mishpat 292;21. See also Shulchan Aruch, Yoreh De’ah 177:19.

[7] Shulchan Aruch, Choshen Misphat 67:9