Imports during shemitah

Imported produce: A farmer's wife speaks

This article is about the halachic aspects and practical ramifications of imports. But let us open with a personal anecdote from the time I (Shoshan) worked at a local farm on a moshav, nearly a decade ago. I was hired as a translator to communicate and work with vendors from abroad and explore options of importing certain types of produce for sale in Israel.

I asked the farmer's wife when she hired me: "Why on earth do you want to import produce? You grow it right here in your field!"

She replied: "My husband loves the land and loves to grow fresh produce. But I'm not sure we'll be able to keep doing this. You see, it's much more expensive to grow vegetables here.

Water is expensive, labor is expensive, and just to produce a beet is more expensive than what it costs to import one, and that's before we even make a profit."

Needless to say, I was floored.

She went on: "The major supermarkets sell imports from Turkey and elsewhere with plenty of rain and cheap labor, and so the produce costs much less. Customers are getting used to paying less, so supermarkets don't want as much local produce. Zionism is nice and all, but we want to survive."

The imported tomato and shemitah

Eli Cohen-Mugrabi, Director of the Joint Agricultural Committee for three local councils in the Northern Negev, explains how the shemitah year serves as the catalyst for the upwards trend in imports and leaves a lasting scar on Israeli agriculture in years following shemitah. (Tu BiShevat Conference 5781, Torah VeHa'aretz Institute):

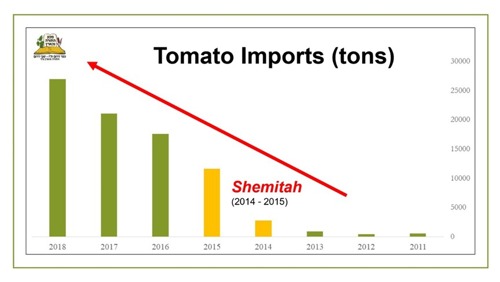

The past seven years have seen a major spike in imports for tomatoes, cucumbers, onions, apples, pears, and even grapes (at certain seasons). While shemitah is not the only factor involved in this trend, it certainly has a major role.

Before last shemitah (2014), only 1,500-2,000 tons of tomatoes were imported, as compared to 2020, where 40,000 tons are imports (annual national consumption today is 160,000 tons; that's 25% imports!).

How did this happen? The Ministries of Agriculture and Finance decided to open exports for tomatoes with a marginal customs tax (90 agorot-1 shekel per kg). Once supermarket chains saw it was possible to import cheaply, they continued in later years.

Most imported tomatoes come from Turkey.

Why is it cheaper there?

Manpower is $3-5 per day

Land is free

Water is close to free

In contrast:

Israeli tomatoes are more expensive to produce:

Manpower is 6-7,000 shekels a month (including medical coverage, benefits)

Water is expensive

1kg of tomatoes costs 3-4 shekels to produce in Israel

As a result, Jewish farmers are being told by supermarkets that they won't be able to sell their tomatoes. That's why before last shemitah there were 3,000-4,000 dunam of tomatoes grown in the Northern Negev, and now there are only 1,000 dunams growing tomatoes.

If last shemitah there were 100,000 tons of imports (2014), and this number has been growing ever since (see the chart), this shemitah we can expect 200,000 tons of imports.

If this trend continues, we will be moving towards becoming an import state, which can endanger Israel's food independence (we don't want to have to give in to Erdoğan on security issues so that we can eat salad).

Of course, the data above is not a reason to violate shemitah laws, G-d forbid, but it certainly does weigh into the overall halachic rational when deciding how to most meticulously observe shemitah laws while protecting Jewish agriculture and Israel's food independence.

Imports during shemitah in the times of the Mishnah

The Jerusalem Talmud notes (Shevi'it 6:4) that importing vegetables was initially prohibited during the shemitah year.

Why was this?

Chazal were concerned that if imported produce would be available and sold, people would also sell local shemitah produce and not handle it with kedushat shevi'it.

This, coupled with the decree against eating sefichin, brought about a situation where Jews could not eat vegetables during much of the shemitah year. References to how the Jews were basically on the threshold of starvation during this year can be found in Talmudic literature (eg. Eichah Rabbah 17).

In light of this, the Sages would avoid making the shemitah year a leap year, so that this challenging year would not be any longer than it had to be (Sanhedrin 12).

R' Yehudah HaNasi worked hard to ease the plight of the Jews during shemitah and employed leniencies when possible. Along with defining certain areas as exempt from shemitah prohibitions, such as Beit She'an, Beit Guvrin, Cesaria, and Kfar Tzemach, he also permitted importing vegetables.

This decision significantly improved the Jews' quality of life during the shemitah year.

At this point, it became possible to add another month to the year, and until today (like this year) shemitah can be a leap year. What about the problem Chazal were concerned with in the first place, about imports mixing with local produce?

Imports during shemitah in Mishnaic times and today

So we discussing how Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi permitted the import of produce. Note that the leniencies he employed (imports and otherwise) were due to the fact that in his time, following the destruction of the Second Temple, shemitah was rabbinic.

Nevertheless, Chazal were concerned that people would come to buy and sell shemitah produce regularly, if this was permitted for imports.

For this reason, it was decided that imports would be handled in a special way.

It was forbidden to sell them:

By weight

By number

By amount (liter, gram)

Rather, they would be sold in an approximate manner.

This begs the question: Why are we allowed to buy and sell imports regularly today?

Rabbi Kook says that this is because today most produce in Israel is heter mechirah and does not have kedushat shevi'it. It makes no sense to treat imports in a special fashion to account for a small amount of sacred produce.

Rabbi Mordechai Eliahu adds that even those who do not rely on heter mechirah benefit from it, since it makes it halachically possible to buy and sell imported produce regularly.

Other posekim (including the Chazon Ish) hold that it is possible to buy and sell imports today since most stores that sell imports or yivul nochri don't sell produce with kedushat shevi'it, so the produce will not be confused.